Industry 1914 - 1919

Brantford’s contribution on the battlefield was matched by its efforts in the factories during the Great War. After the initial economic slump, which threatened the future of some businesses, war contracts began to invigorate the economy once again. As the war progressed, labour issues arose, sometimes resulting in conflict between workers and management. However, the strong reputation of Brantford industry remained intact. Ultimately, by war’s end, the spirit of industrial cooperation was in jeopardy. One important manufacturer sought to restore it through the creation of the Chamber of Commerce

1914: Shock and Recovery

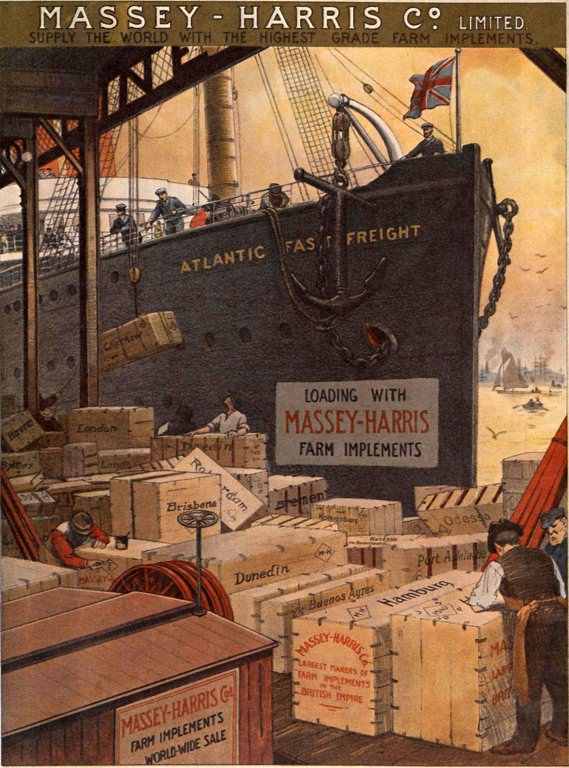

By early August, word had spread of an impending conflict in Europe. Industry was going to be affected, but no one could quite articulate how it would impact the economy. The fact that Brantford was the third largest exporter in the country made many industrialists and their workers nervous of the impact the war might have. There were reports that many Brantford businesses, including Massey-Harris, Cockshutt, and Brantford Cordage, might be negatively impacted by a conflict in Europe.[1] This fear was not unfounded, as these manufacturers had lucrative contracts with countries such as Germany and Russia. The war made Canada’s industrial sector, including Brantford, apprehensive.

By late summer, several companies had already been forced to close, lay off workers and severely limit production: Brantford Cordage, Brantford Cut Glass Company, Keeton Motor Company, and Massey Harris were among those affected.[2] Still, Brantford remained invested in the war both in terms of men and materiel and it was the industrialists who championed the local economy. Despite the economic hardship they endured, the industrialists of Brantford wholeheartedly supported the war. They were vocal in the newspapers and in their actions. Retailer E.B. Crompton was quoted on August 6, 1914 saying that “there never was a time when the nation was more united or more unanimous for war than the British nation is at the present time. Now is the opportune time to put an end to the pretentions of the German Emperor.”[3] Harry Cockshutt’s donation of a carload of army wagons[4] and the $50 bonuses that Massey-Harris gave to workers who volunteered for service demonstrated the level of support Brantford businesses gave to the very war that negatively affected them.

Despite the economic slump that the beginning of the war induced, the tide quickly turned. A deputation of local politicians and industrialists who went to Ottawa to petition for war contracts generated results. Slingsby Manufacturing Company won a contract for blankets for the navy and Adams Wagon Works received one to produce army wagons. This boosted Brantford’s economy.[5] Eventually, other businesses started to see similar returns; the Kitchen Overall and Shirt Company was awarded a large contract for the army and the Brandon Shoe Company received a contract for 5000 pairs of army shoes. The improvement in outlook resulted in labour organization, with the Brandon Shoe Company soon becoming a ‘union shop’.[6]

Brantford industry became highly regarded for its quality workmanship. Confidence in the products coming from Brantford bolstered the economy; the British War Office had a preference for Canadian wagons and stated they were “‘the most serviceable wagon ever made for military transport purposes.’”[7] A successful wartime economy was in the works. In fact, by the end of the year, there was enough confidence in Canadian products that a ‘Made-in-Canada Movement’ prompted the creation of several American branch plants in Canada. This would result in the training and hiring of more Canadian workers.

By 1915, the tone of a Brantford Expositor editorial written in the New Year was downright ‘optimistic’ about the economy. In the piece, entitled, “Time to Cheer Up”, the editor predicted confidently that the Germans would lose the war and that, despite the ‘severest trials’ at the beginning of the war, the local economy was recovering. “We cannot pass through such a tremendous world war,” he declared, “without feeling it, and for a while we will all have to curtail our luxuries and pay closer attention to business, but individually we will be benefitted by the experience. Let’s cheer up.”[8]

1915: War of Attrition

Lord Kitchener, Britain’s ‘Lord of War’ set the tone for industry in Canada by 1915:

I have said that I would let the country know when more men were wanted for the war. The time has come, and I now call for 300,000 more recruits to form new armies. Those who are engaged in the production of war materials of any kind should not leave their work. It is to men that are not performing this duty that I appeal.[9]

At this point in the conflict, having a strong industrial base was as important as having good men at the front. Furthermore, Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia, impressed upon the Dominion Shell Committee that all components of the shells to be used on the front be produced in Canada. Brantford would meet this call.

Industrial contracts were secured through the exhaustive efforts of local politicians and the Board of Trade for the city. Several trips, not only to Ottawa, but to the 'Old Country' were made to impress the Dominion Shell Committee and the Minister of Militia. These contracts were very difficult to come by as there was a very strict set of conditions and standards which had to be met, but again, the demand was for locally produced munitions.

Industrial contracts were secured through the exhaustive efforts of local politicians and the Board of Trade for the city. Several trips, not only to Ottawa, but to the 'Old Country' were made to impress the Dominion Shell Committee and the Minister of Militia. These contracts were very difficult to come by as there was a very strict set of conditions and standards which had to be met, but again, the demand was for locally produced munitions.

Local politicians and businessmen were tireless in securing contracts: Keeton Motor Company, Cockshutt Plow Company, Slingsby’s, Mayor Spence and W.F. Cockshutt, M.P. were all instrumental in personally securing meetings with the Minister of Militia. This proved a successful strategy. A sub-committee of the Board of Trade of Brantford’s City Council even passed a resolution in August to use “every legitimate means to bring war orders [to Brantford].”[10]

Industry in Brantford started to pick up in the areas of shell production, wagons and war transport trucks throughout the year. By the summer of 1915, the agricultural implements industry saw some relief with a large harvest predicted for the fall and the return of French farmers to their fields. The result was a boom for implements manufacturers, especially Massey-Harris. This prompted H.H. Powell, the President of the Board of Trade, to state in March: “Brantford has not reaped the great benefits from war orders as some other cities, but they are gradually coming this way … with the big harvest in the west this year, good times should come to this city.”[11]

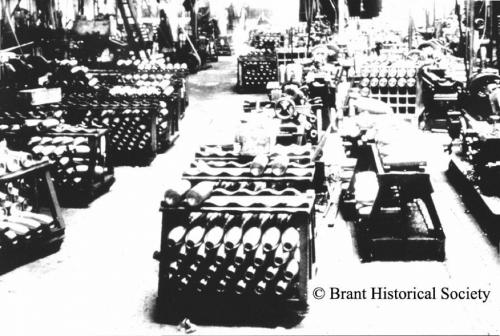

The large bulk of industrial growth in Brantford during this year came from the production of shells. By June of 1915, there were 247 Canadian companies producing shells; Brantford had secured one of those contracts, but more were to be won. By the end of the summer, there was an expectation of having Canadian companies producing 40,000 to 50,000 shells per day.

The Steel Company of Canada was one such factory, with Ker and Goodwin Ltd., Waterous Engine Works, and Goold, Shapley and Muir (demand of 35,000 shells) gearing up for production. John H. Hall and Sons prepared for the surge in demand by manufacturing the machines to produce such shells (lyddite shells). This also included the production of shrapnel shells, specifically the British 18-pounder, 3.3. The most successful contract to be secured was by the Steel Company of Canada which totaled 2/3 of a $20 million contract to produce shells for the Dominion Shell Committee in late 1915. Similarly, the Waterous Company also secured contracts to produce shells that year.

Brantford was not alone in its industrial success and employment levels across the region increased. The Old Town Hall in Paris was converted into a machine shop by the G.W. McFarlane Engineering Company to produce shells. B. Bell and Son Company in St. George secured a contract to manufacture shells and there was a flurry of hiring by the summer. Machinists were in demand and factories ran full-time, with workers working double shifts or “as much as the law allowed.”

Brantford was not alone in its industrial success and employment levels across the region increased. The Old Town Hall in Paris was converted into a machine shop by the G.W. McFarlane Engineering Company to produce shells. B. Bell and Son Company in St. George secured a contract to manufacture shells and there was a flurry of hiring by the summer. Machinists were in demand and factories ran full-time, with workers working double shifts or “as much as the law allowed.”

Despite the rise in employment, some people were concerned and Imperialist tendencies reared their heads. In a letter to the editor, a citizen named Lloyd Garrison wrote to complain about the number of ‘enemy aliens’ who were employed in Brantford factories while “white” (Canadians and ‘Britishers’) were unemployed. The ironic tone in the pleading question was not lost: “Is this a ‘patriotic’ move on the part of the directors, managers, and superintendents? It is a disgrace to civilization.”[12] An investigation by the mayor was demanded, but never materialized. Despite small setbacks like a tariff increase of 7.5% and a one-day strike by women[xiii] at an envelope factory, the year 1915 was one of incredible economic and industrial success for the area.

1916-1917: War Fatigue and Its Impact

Between 1916 and 1917, there were high expectations placed upon labourers in the industrial sector. Unionism, agricultural demands, racism under the guise of the ‘enemy alien’ moniker, and increased demand to meet industrial contracts and quotas all contributed to tension in Brantford’s labour market. All of these concerns intersect in the lives of the average Brantford labourer.

There was a growing contradiction between demand for workers and a fear of the ‘foreigner’ in 1916. The reason for this was a natural tension between the desire to maximize production and suspicion of outsiders. While Brantford was seen as an industrial hub, the number of orders coming into the city paled in comparison to relatively smaller municipalities.

In January of 1916, The Brantford Expositor reported that local contracts with the Canadian Shell Committee (up to September 1st of 1915) totaled $625,700. Compared to Galt ($3.4 million) and Dundas ($1.9 million) Brantford appears to have been left only a small portion of the wartime industry ‘pie’. Even Paris, Ontario, with a significantly smaller population was ‘pulling its weight’ with a total of $90 000.[14]

Even as fears mounted that Brantford was lagging behind other manufacturing cities, fear of foreigners grew. This fear was evident in a letter to the editor written by W.B. Johnson in February of 1916. He wrote:

I am not wishing to arouse race animosity, but it has just come down to this that Germans and Austrians have demonstrated worldwide that they cannot be trusted and the sooner Canada realizes this the less we are going to be terrorized by their cult.

The paranoia is clear and was justified by the author as he was “doing [his] bit for my King and Country.”[15]

This struggle between bigotry and the desire to contribute industrially is clearly illustrated in an interview with C.H. Waterous in February of 1916. In this interview he responded to questions about whether or not he was employing ‘enemy aliens’ at the works. Waterous defended hiring ‘men such as these.’ He gave a reasoned argument that these men were ‘induced’ to immigrate by the Canadian government and had been employed since before the war broke out. He also maintained their loyalty to the cause, noting “We have had the men in our employ since long before the war. They have never shown any disposition to be disloyal to this country…”[16] Waterous then gave several examples of men who had been employed in the factory for several years and who had family fighting for the Entente. One particular example was a man who had been in the factory for 20 years, a Canadian citizen for 15 years and whose family lived in Paris. This man had nephews who were “fighting with the gallant French army, which is with the British.”

But, Waterous was very quick to point out that there were no German-born men employed with the factory, that only ‘Canadian Germans’ or ‘Pennsylvanian Germans’ were employed, one of whom had been with Massey-Harris for over 25 years.

Waterous admitted to employing Armenian, German and Russian Poles and Galicians (a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) – because they were doing the work that no one else would do. He argued that these men harboured no loyalty to their “rulers or oppressors” (Turkey, Germany and Austria-Hungary respectively). In fact, Waterous made the statement that if he didn’t hire these men they would surely be “turned out to starve or to be placed in internment camps.”[17]

C.H. Waterous saw himself as a savior of these men, performing acts of social welfare and community-building. He argued that these men had been employed because their work could have be done by ‘ordinary men’ (white Canadians and British), “but where were they to be found? All the available men were employed or were going overseas.”[18]

Similarly, workers recognized that they were a vital part of the war effort and responded with demands. The labour movement added to the tensions that existed. In March of 1916, moulders at Pratt and Letchworth Company walked off the job to demand a 10% wage increase. The employer promised 5% immediate pay raise with an additional 5% if quota was met.

Similarly, workers recognized that they were a vital part of the war effort and responded with demands. The labour movement added to the tensions that existed. In March of 1916, moulders at Pratt and Letchworth Company walked off the job to demand a 10% wage increase. The employer promised 5% immediate pay raise with an additional 5% if quota was met.

In May of the same year, there was a strike at the Waterous Engine Works Company.[19] In that same month, the Machinists’ Union at Massey-Harris wanted to ensure that the men who had worked there but left their jobs to enlist would be guaranteed employment upon their return.

Concern was raised over ‘temp’ workers being brought in from Quebec and being paid less than the workers they replaced. There was a rumour that these workers would stay on at a lower wage and those who had enlisted would return to find their jobs were taken.

With men serving in large numbers, the need for workers also increased. Massey-Harris had agents in “‘every town in Ontario and Quebec to recruit suitable labor.’”[20] The shortage of labour allowed the workers who were employed to demand better wages and working conditions.

The labour crisis was underlined in an editorial in August of 1916. The Brantford Expositor claimed that “the ‘local industrial situation is, in some respects, far from being satisfactory. There is no scarcity of orders, on the contrary; more business is offering that the factories are able to turn out. The chief trouble is scarcity of labour.’”[21]

Industrial contracts, then, were absolutely vital to Brantford’s role in providing munitions and materiel for the war. By July 1916, industrial contracts were increasing and this placed more demand on the population for jobs in factories. Dominion Steel Products Company was incorporated and responsible for manufacturing 9.4 inch shells.

The added bonus of securing this contract in Brantford was that it was to continue on as a factory in another manufacturing capacity after the war was over. Several other communities vied for the same contract and the manufacturers committee of City Council met with representatives of the company to lobby in Brantford’s interest. By the fall of 1916, the Dominion Steel Products Company was erected on Morrell Street and was touted as “a decided asset to the city of Brantford.”[22]

Labour unions in Brantford began to truly make their influence felt in 1917. As conditions took their toll on the average labourer, the unions used opportunities to organize. While management in factories were pressing their workers for more, the labour movement sought improved conditions. In May 1917, moulders and coremakers demanded a 9-hour day, but with wages equaling to 10 hours of paid labour. Manufacturers agreed, but not during times of war so as to “disturb industrial conditions.”[23]

The workers threatened a strike and on May 21st none of the men arrived to work. In total, 300 men walked off the job. One manufacturer explained that they did not meet the demands for fear of losing the contract to another firm which “could get castings outside the city cheaper than they could produce them.” The workers argued that no discussions were taking place, hence the walkout. These labour issues were not deemed to be serious at the time and there was a hopeful tone at the end of the article on the strike: “There is still a feeling that an agreement mutually satisfactory to both parties will be arrived at.”[24]

This tone changed with the arrest of Mike Koenig, an Austrian worker who was charged with intimidation of a ‘scab.’ On the 28th of May Koenig issued a death threat to John Phillips if he “dared to carry out his intentions, against the will of the strikers.” The labour movement at this time was a collective effort. Koenig, while charged, was not the only one present when the intimidation took place. These other workers presented evidence in Koenig’s defence and they issued an appeal of the magistrate’s imposition of a $100 fine (or 3 months in jail). Since the decision was under appeal, Chief Slemin released Koenig and then re-arrested him moments later. A new charge, of being an ‘enemy alien and dangerous to be at large’ was laid.[25]

What had started as a labour issue, quickly evolved into one of race. By June of that same year, the workers were still on strike. This is significant in that demand remained at an all-time high. The stoppage of work had a tremendous impact on Brantford’s overall output and reputation. One manufacturer stated, “It will be hard on the city of Brantford if these men are let go, and it will give Brantford a bad name amongst other places and manufacturers who might want to come here.”[26] Massey-Harris and Verity Works conceded 5% increases eventually. The impact of these increases was felt by over 1,000 workers at these two factories – clearly a victory for the labour movement in Brantford.

The issue of ‘unionism’ continued to fester. In June, Mayor Bowlby wrote a letter to Col. A.P. Sherwood, Chief Commissioner of the Dominion police and head of the ‘alien enemy department.’ He argued that another Mike, this time Mike Konik, had been wrongly imprisoned. He was Russian, and therefore ‘friendly.’ Bowlby also urged the Chief Commissioner to remember the values upon which Canada had been founded and for which we were fighting:

I have always regarded Canada as a free country, and because we are at war it does not make it less so. I am no labour unionist, but I think that unions in common with other people have rights and if so minded to strike to better their condition, should be a liberty to do so.[27]

The Mayor went on to support the striking moulders, describing the shop at Pratt and Letchworth as a “perfect inferno… with its sulphuric acid gas, smoke, heat and general abomination.” He argued that the police chief was confusing the labour movement with ‘enemy alien’ concerns and added “I now take the liberty to assert that this city, which has contributed in, proportion to its population, more men and more money than any spot under the sun, should not on war account lend itself … to manifest wrong and injustice.”[28]

The labour shortage continued into 1917 and became all the more severe given the need for men on farms to assist in the agricultural sector. In other cities, men were often removed from factories to work on farms. The labour crisis in Brantford did not allow Brantford to follow that pattern. A superintendent of a local plant stated that they were “handicapped through lack of competent help... and would gladly accept from 25-50 good men at this time, rather than discharge a single man now in our employ.”[29]

This labour shortage was a serious concern to all members of the Board of Trade, which gathered in June 1917 to discuss the issue. There was an attempt to persuade the manufacturers of Brantford to help more readily with the agricultural sector in Brant County. In an attempt to keep them on board with the plan, it was suggested that, rather than remove workers from the factories, they be encouraged to undertake extra work on farms. The manufacturers then unanimously passed a resolution that: “all employers of help in Brantford be sent a copy of this resolution, and that they be urged to lay this before their employees, with the object of securing as far as possible all available help…” The ‘who’s who’ of Brantford’s industrial sector – Cockshutt, Scarfe, Brandon, Schulz, Muir and Waterous – endorsed this resolution.[30]

Additional factors which would give rise to labour strife include the reduced output of 4.5 shells. This reduction affected many Brantford factories like Ker and Goodwin, Waterous Engine Works, Motor Trucks Limited, Gould, Shapley and Muir. Production at some local factories was limited to only 40% of pre-war production and, as a result, many workers were laid off. For some shops, this totaled a nearly 50% reduction of workers and resulted in roughly 160 single men being laid off.

These men found work in other factories or went to the country to help with the agricultural sector in September. Some even went to Prairie Provinces such as Manitoba to help with the harvest. Other individuals, despite their best efforts, could find no work at all. The labour market bounced back by December. An addition to the Brantford plant of the Steel Company of Canada resulted in a 50% increase in floor space and increased labour capacity by 50%.

Meanwhile, with the entrance of the United States into the war in April of 1917, Canada was primed to support its allies. The US government issued an order of 75 mm shells with additional orders for ‘peace business.’ This increase in industrial contracts was thanks to a ‘branch plant’ system stemming from a campaign launched in 1917 by the municipal government’s manufacturers committee.

Labourers in Brantford were torn between loyalty to their unions, their employers and the war effort in general. This, combined with serious health and safety concerns (crushed arms, toxic fumes and gas fires), created a perfect storm in which the labour movement could take hold.

1918-1919: Bolshevism, Sedition and Terrorism

Two themes emerged as Brantford moved into the post-war period: the rise of Bolshevism, and the urgency of industrial ‘readjustment’ championed by the newly formed Brantford Chamber of Commerce.

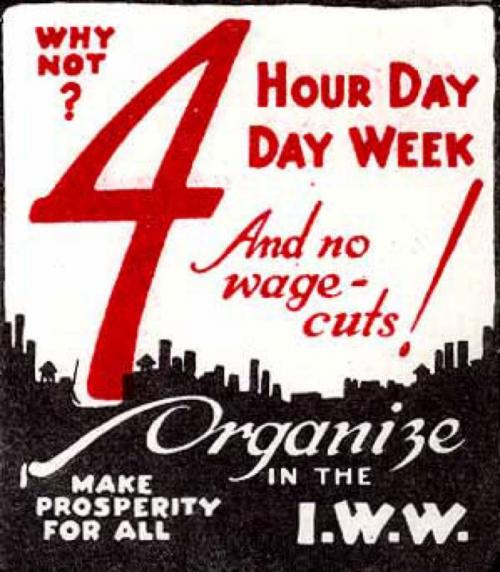

The fear of the foreigner was intensified by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the resultant Russian Civil War, which pitted the Whites against the Reds. Fear of Bolshevism virtually replaced fear of Germans as Germany’s surrender became all but inevitable. This fear of Bolshevism was closely tied to the fear of labour activism – which had been an irritant in Brantford during the war. Suspicion of labour activism culminated in a banning (through an Order in Council) of all publications by the “Wobblies” or the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World), a labour organization whose main goal was to empower workers through unionism.[31]

Another layer of complexity related to the fact that many Eastern European immigrants were blamed for spreading the ideas of the revolutionaries in Europe. Consequently, it was a convenient moment to target immigrants as well as labour leaders, particularly those with Eastern European roots.

In July 1918 the following short article appeared in The Brantford Expositor which reflected this fear:

That there is an insidious pro-German propaganda in existence in this city, more insidious because it is cloaked in the form of crude appeal to labor, was evidenced this morning when a one-sheet pamphlet was being distributed by boys in some of the local factories, urging workingmen to get behind the movement for a four-hour day. The pamphlet had all the earmarks of the I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World) upon it, and Tom Mann and Karl Marx were quoted and revolution frankly urged. Any time a man works longer than the four hours per day, the capitalist employer gets the surplus, it stated. The idea, of course, was for the worker to work just long enough to keep himself, and not more. The whole thing looked a bit of nauseous vapor from the Russian plot of Bolshevism. An appeal to class hatred, an appeal of a very low order, the pamphlet proves on examination, doubtless with an effect on the unenlightened, particularly those from the eastern centres of Europe. The who is so obviously pro-German in its motive that the circulators, if apprehended, would doubtless be in for a serious time with the authorities. The matter has been reported to police.[32]

Fear of socialism was not confined to Russia. Germans were also targets of suspicion as a result of what was happening in Germany with the rise of workers’ parties and groups such as the Spartacist League. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in October of the previous year indicated a burgeoning world-wide labour movement that threatened the industrial capitalist economic system upon which Brantford had built its reputation.

Fear of socialism was not confined to Russia. Germans were also targets of suspicion as a result of what was happening in Germany with the rise of workers’ parties and groups such as the Spartacist League. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in October of the previous year indicated a burgeoning world-wide labour movement that threatened the industrial capitalist economic system upon which Brantford had built its reputation.

All of these fears fell on the shoulders of a naturalized Russian by the name of Felix Consevitch. He was a worker at Waterous Engine Works who was caught with ‘objectionable literature.’[33] He was given the choice of accepting a $500 fine or serving a one-year sentence in the Ontario Reformatory. Since the mean wage of an immigrant factory labourer was approximately $17 per week by 1921,[34] the fine would have been impossible for him to pay.

John H. Hall of Messrs. John H. Hall and Sons of Paris, provided evidence that led to his conviction. Before the sentencing, the judge allowed Consevitch to speak to his crime. The Brantford Expositor could not resist editorializing as it described the statement of the accused. Consevitch:

…opened up a real ‘soap box’ oration of the Bolshevik kind. Equality of all men was advocated. Let the shopkeepers all get to work, let everybody work and only four hours per day would be necessary for everyone. Consevitch waved his hand at the legal talent in court as he insisted everybody working. School teachers should also work, and then everyone would have time to teach their own children. It was a crude doctrine which the prisoner preached.[35]

The views were, in fact, presented and explained as ‘anarchistic’ and Consevitch was deemed a pawn placed in Canada by the ‘pro-German socialists of the East.’

The judge’s comments regarding the actions of Consevitch were decidedly patriotic in tone. As the reporter noted, the judge explained that “‘anyone advocating a four hour day when people were working night and day to defeat the common enemy, was certainly endeavoring to detract from the Allied effort.’” The judge then publicly declared that this sentence was a message for anyone else thinking of echoing the ‘four-hour work day’ protest: they would be found guilty as well.

Consevitch was not the only person charged with sedition. Five more Russians (including H. Moroz, John Slobodian, John Gruscitski, Artine Kusmitch and Alex Barrell) were charged with having ‘objectionable literature’ and two were found guilty by Mayor MacBride. Artine Kusmitch and Alex Barrell were each fined $500 and sent to the Ontario Reformatory for 6 months. If they could not afford the fine, then they would serve an additional year beyond the 6 months.

Charging these men as a group was not difficult since they all resided in the same property on 18 Sydenham Street. More than likely, they would have lived there on ‘shifts’ as they worked in the factories. Most shift-worker homes were organized on the basis of double occupancy, which involved the sharing of beds by workers on opposite shifts.

The tone around labour activism had changed in Brantford, and Canada more broadly. As socialist literature became more inflected with ‘revolutionary’ rhetoric similar to what was being seen in Russia and Germany, the government’s fears appeared to be justified. In the Consevitch case, the judge – who was also Mayor of Brantford – used his discretion to maintain order. This was all the more surprising given that Mayor MacBride was an avowed supporter of labour!

The critical context is that people were tiring of war and wanted the end to come quickly. Any measure that could reduce unneeded ‘drama’ in the workplace was applauded. Mayor MacBride was quoted as saying that “socialism might be good for Canada and other countries, [but] there was a time for everything, and this time the main business was the prosecution of the war…” He went on to emphasize that “…propaganda was being furthered to divide Canada, and foreigners should be careful. They should cease to encourage in Canada the doctrine they had brought from Russia.”[36]

The rising anti-Bolshevik sentiment was met with resolve by the Russian community. In January of 1919, it was reported that Russians had banded together to raise money to pay the $500 fine that Consevitch had had levied against him as “Consevitch’s wife and children would have been destitute otherwise.”

The Russian community even placed advertisements in a Winnipeg newspaper to help raise funds. This information stems from a news report in The Brantford Expositor which details another court case dealing with the ‘Bolshevik problem.’ The report identifies Brantford as a “headquarters of Bolshevik advocates in Canada.”[37]

One such ‘leader’ was a man named Andra Tretjak who was arrested for ‘being a member of unlawful assemblage and seditious conspiracy.’ He was found guilty of ‘being a member of an unlawful society’ based on evidence that was described as ‘contradictory.’[38] He had been living in Brantford since 1912 and was employed at Malleable Iron Works throughout the war.

What raised alarm bells for local authorities was that he was connected, loosely, to Consevitch. Simply, he was raising money on his behalf. He was found guilty on account of some letters he had written. Some letters had been addressed to ‘Comrades’ and had featured acronyms like S.R.R. (which was interpreted as the Union of Russian Workers) and the stamp of A.K. which was interpreted as “Anarchism and [K]ommunism.”

In all likelihood, the acronym A.K. stood for Alexander Kerensky. Tretjak had admitted to “attending Kerensky meetings on several occasions” but “He repeatedly denied having any connection with Socialist or Anarchist organizations.” The sedition charge was withdrawn; however, he was sent to jail for 3 months for “being a member of an unlawful society”. After three months he was offered the opportunity to return home, provided he paid a $1,000 fine.[39]

Readjustment in post-war industries

At the end of the war, Brantford’s captains of industry prepared for the transition to peace. In June of 1918, housing developments were planned specifically for the workers and their families. W. S. Brewster of the Dominion Steel Products Company saw this as a way to secure workers from outside of the city.

In November 1918, The Brantford Expositor interviewed all of the major manufacturers in Brantford and asked them how they planned to transition from a war-time to a peace time economy. Each manufacturer was granted a paragraph in the article.[40]

Mr. J.W. Verity of Verity Plow argued that any lull in productivity caused by the cessation would be temporary and that “‘Brantford was better fixed than most centres for a rapid recovery.’”

C.A. Waterous of Waterous Engine Works looked to the future as an opportunity to help with ‘replacement’ after the war, noting “Brantford was better organized than most cities for the change or transformation, and that recovery would be quick in this city.” John Muir representing Goold, Shapley and Muir, “…believed that there was a better feeling between employer and employee than had formally existed”. Dominion Steel’s W.P. Kellett said: “We are organized for peace, if peace is declared today we do not expect that there will be a single day of stopping work in our plant.” Finally Col. Harry Cockshutt of the Cockshutt Plow Company, noted that he expected an increase in business because of the demand for more agricultural implements.

After the Armistice was declared on November 11th, there was no immediate cessation of war production. By the 14th of November “the director of one of the biggest munitions firms in Brantford stated…that no word had been received or was expected.”[41] Even by November 26th, 110 carloads of 9.5 shells were ready to ‘nose.’ Factory activity seemed to be continuing as though the “circumstances of the contract were unchanged.”

By November 28th word was finally received of cancelled American contracts with the Steel Company of Canada. The factory was expected to close shortly after that date, resulting in 300 lay offs. Previously, the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association had placed an embargo on any orders to other countries, in order to secure all production for the Canadian and British armies. By November 29th, this regulation was relaxed. Contracts overseas, notably with South Africa, South America, Australia, New Zealand and the Far East, were permitted. While some people were losing their jobs, Massey-Harris opened their doors to new employees, welcoming nearly 80 men per week by November 30th.

The rumour was that men had been ‘discharged’ or laid off from munitions factories in Dundas, Paris and Toronto. This never happened in Brantford. No more than 2 firms in Brantford were expected to lay off workers because “‘this city is thought to be in a particularly good position by reason of the fact several munitions firms changed over to peace-time production and got very busy on the same before the end came.’”[42] By December 3rd government employment bureaus were placing men in jobs in large manufacturing plants, which were in need of skilled workers and mechanics.

The Siberian Expeditionary Force was used against the Reds in Russia’s Civil War between 1917 and 1919. Canada’s industry supported the Force until its removal from combat in June 1919. Industry would produce war materiel for over half a year beyond the signing of the Armistice. Events in Russia had been overshadowed by the European war. However, on December 3rd of 1918 it was reported by The Brantford Expositor that an anonymous manufacturer in Brantford was hopeful that “Russia would open up great possibilities” under a stable government.[43]

The Siberian conflict was just one factor that seemed to indicate that Canadian industry might well prosper in the future. However, this confidence was tempered by concern that returning veterans might be infected with socialist ideas. This ambivalence was reflected in The Toronto Mail and Empire on January 14th It included an article featuring an extensive interview with “one of Canada’s leading businessmen”, Col. Harry Cockshutt. A “strong advocate of the community spirit,” Cockshutt declared that the spirit of cooperation was essential to post-war prosperity.

I am certainly very optimistic regarding the future of my own business…but so far as the general situation is concerned I am perhaps not so certain. There are many problems to be faced that will have to be seriously considered. At present there is a great feeling of unrest throughout the country. Different classes and groups are propounding different ideas. But the manufacturer and the worker must not be antagonistic. Cooperation to the fullest extent on the part of both is absolutely essential to make for prosperity. Neither must the agriculturist be antagonistic to the worker or the manufacturer, and vice-verses…

In a country as young as we are, we have reason to congratulate ourselves on our advancement in all lines of commerce. And for the future we should have an absolute community of interest. There should not be any feeling that one class is antagonistic to the other. We can accomplish much and go far and prosper if we foster a better spirit and work for the interests of Canada and the united people. I am strongly of the opinion that the worker and the proprietor should act in harmony and that consideration and sentiment should bring them together.[44]

One solution to the dilemma suggested by Cockshutt that was favoured by business leaders was the creation of a Chamber of Commerce. The Expositor of January 15th 1919 argued “Brantford deserves a civic-commercial organization of the finest kind, strong enough to handle all the readjustment activities promptly and in the way desired by the citizens and the government.”[45] More important still, however, was the need to compete with similarly-sized municipalities for manufacturing and industry (such as Stratford, St. Thomas, and Guelph). These cities were cited as examples of ‘organizing’ cities against whom Brantford would have to compete in the post-war period.

[1] The Brantford Expositor, August 1, 1914.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Brantford Expositor, August 6, 1914.

[4] The Brantford Expositor, August 26, 1914.

[5] The Brantford Expositor, August 24, 1914.

[6] The Brantford Expositor, October 30, 1914.

[7] The Brantford Expositor, November 11, 1914.

[8] The Brantford Expositor, January 6, 1915.

[9] The Brantford Expositor, June 19, 1915.

[10] The Brantford Expositor, August 31, 1915.

[11] The Brantford Expositor, March 6, 1915.

[12] The Brantford Expositor, December 2, 1915.

[13] The Brantford Expositor, February 10, 1915.

[14] The Brantford Expositor, January 18, 1916.

[15] The Brantford Expositor, February 10, 1916.

[16] The Brantford Expositor, February 9, 1916.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] The Brantford Expositor, May 6, 1916.

[20] Ibid.

[21] The Brantford Expositor, August 31, 1916.

[22] The Brantford Expositor, September 25, 1916.

[23] The Brantford Expositor, May 19, 1917.

[24] The Brantford Expositor, May 21, 1917.

[25] The Brantford Expositor, May 30, 1917.

[26] The Brantford Expositor, June 2, 1917.

[27] The Brantford Expositor, June 19, 1917.

[28] Ibid.

[29] The Brantford Expositor, April 21, 1917.

[30] The Brantford Expositor, June 14, 1917.

[31] “The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or Wobblies were a radical union organization. In comparison to trade unions, the Wobblies aimed to organize all workers in an industry, skilled and unskilled, native and immigrant, men and women. Wobbly theorists believed that industrial unions were eventually to give way to one “grand” or “big” union, in order to unite against capital... Although the economic downturn of 1913-1915 and World War I eroded Wobbly strength, however, their history testifies to the tension created by industrialization in Canada, and to the very different ways that various elements within the working class responded to such tensions. The Wobblies popularized the idea of the “grand industrial union” and the “general strike,” both of which would guide Canadian workers-skilled and unskilled-in their protest against social conditions at the end of World War I.” http://blogs.ubc.ca/mannis2/tag/winnipeg-general-strike/. For a more complete history of the IWW see “Workers Unite: Industrial Workers of the World” Canadian Museum of History, accessed August 19 2014. http://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/labour/labh17e.shtml

[32] The Brantford Expositor, July 9, 1918.

[33] The Brantford Expositor, July 16, 1918.

[34] If a worker was employed for 50 weeks out of the year, his rough income would be $850 per year, based on a $17 per week wage. A fine of $500 would not leave enough for the family to survive. Consequently, a year in jail would be $850 of lost wages. Alan Green and David Green. “Immigration and Canada’s wage structure in the First Half of the Twentieth Century” (2008) http://qed.econ.queensu.ca/CNEH/papers/GreenGreen.pdf

[35] The Brantford Expositor, July 16, 1918.

[36] The Brantford Expositor, August 31, 1918.

[37] The Brantford Expositor, January 15, 1919.

[38] Ibid.

[39] The Brantford Expositor, January 27, 1919.

[40] The Brantford Expositor, November 5, 1918.

[41] The Brantford Expositor, November 14, 1918.

[42] The Brantford Expositor, December 2, 1918.

[43] The Brantford Expositor, December 3, 1918.

[44] The Brantford Expositor, January 15, 1919.

[45] Ibid.