Agriculture

“Where would your farm be if it were not for these men who have donned the khaki to fight for you?”

Brantford and Brant County illustrated the changing demographics of Canadian society during the war. While Brantford was an industrial leader, Brant County and its supporting communities were inevitably rural. While factories were being retrofitted to produce munitions and other materiel for the front, there was also a burden of increased production on the agricultural area of Brant County and Six Nations. Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations felt the pressure to fill labour in both the factories and the fields, all while still being expected to sacrifice every available young man to the war front.

In September of 1914, local farmers anticipated an agricultural shortfall because of the “European War.” As a result there was an average increase of 10 acres per farm, especially in Onondaga, Mount Pleasant, and Paris areas. Onondaga Township was touted as being the “largest wheat-growing township in the county” with local farmers Robert Oliver and John Painter increasing their farm output significantly to accommodate the war.  The main crop grown on area farms was wheat, with the exception of potatoes in Mount Pleasant. Names of individual farmers were referenced specifically in order to highlight the importance of the agricultural sector.[1] The war also provided conditions for self-sufficiency in agriculture when, in late 1914, farmers were called by the Ministry of Agriculture to produce their own seed. This was in reaction to an unforeseen shortage of root and vegetable seeds. Previously, seed had been supplied by France and Germany, who were obviously in no place to continue this supply.

The main crop grown on area farms was wheat, with the exception of potatoes in Mount Pleasant. Names of individual farmers were referenced specifically in order to highlight the importance of the agricultural sector.[1] The war also provided conditions for self-sufficiency in agriculture when, in late 1914, farmers were called by the Ministry of Agriculture to produce their own seed. This was in reaction to an unforeseen shortage of root and vegetable seeds. Previously, seed had been supplied by France and Germany, who were obviously in no place to continue this supply.

The importance of farmers’ contributions to the war effort was further emphasized in a letter to W. F. Cockshutt, M.P. (South Brant) in 1914:

“an offering should be made [of foodstuffs]…in recognition of their duty and loyalty towards the government of Great Britain in the prosecution of the war and to the relief of distress resulting from there.”

Local farmers were willing to donate this food if the British government was to cover the cost of transporting the goods [from Canada to Europe]. [2]

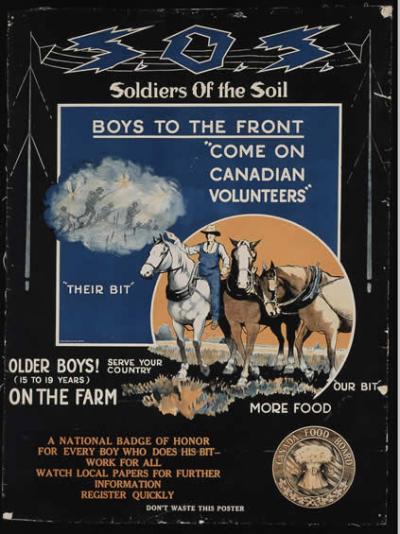

Similarly, Brantford area farmers were able to employ those without work, with some farmers making applications at the City Engineer’s office to take on the jobless in 1914. This sometimes proved difficult for unemployed men who had families to support, as farmers were only willing to take and provide board for single men. By 1915, the need for farm hands was still an issue and the Ontario Employment Bureaus were seeking men to work outside the city. This was so much the case that it actually delayed the harvest. By early 1916, the need for labour on farms was so desperate that invitations were extended to retired farmers. For those men who were not able to physically help, many were positioned as heads of Scout troops who would then go on to become young farmhands (boys aged 15-19), then known as ‘Soldiers of the Soil.’[3] Indeed, every sector of society was encouraged to participate in this vital work during the Great War. Brantford, Brant County and Six Nations felt the burden of a triple-duty to the agricultural, industrial and war fronts.

This burden is best illustrated by the case of a farmer named John Lee of Northfield Center in 1916. So desperate was Lee to keep hired hands on his farm, that he assaulted army recruitment officer Q.M.S. Taylor when he approached a worker on his farm. Clearly, there was a need to ensure that all men were fit for duty, including those working on farms. Lee viewed the recruitment officer as a ‘poacher’ of good farm labourers and reacted accordingly. Lee was reprimanded, and given the maximum penalty for assault by the magistrate (judge), who chastised him: “Where would your farm be if it were not for these men who have donned the khaki to fight for you?”

The issue of a labour shortage on the farms continued through 1917, when the Brantford War Production League, under the leadership of Logan Waterous, prompted an initiative that saw all staff of the manufacturing offices give up their summer holidays to help out on local farms. This policy was reinforced by the summer in anticipation of the fall harvest. In June 1917, a unanimous endorsement of the following resolution was passed by the Board of Trade:

Whereas, it is the opinion of this meeting that the work of the Board of Trade undertaken to assist in securing help for the farmers this summer, is worthy of support and should be gone on with, and that all employers of help in Brantford be sent a copy of this resolution and they be urged to lay this before their employees, with the object of securing as far as possible all available help, filling in the necessary forms and returning them as quickly as possible to the secretary of the Board of Trade.

The weight of this commitment was felt with the inclusion of signatures of important members of the Board: Lieutenant-Colonel H. Cockshutt, R. Scarfe, A. Brandon, W.D. Schultz, John Muir, and C.H. Waterous.

The issues within the agricultural sector were mirrored on the Grand River Territory with the Six Nations forming their own production league in April 1917. Under the direction of Chief Henry Martin, the Six Nations Production League consisted of Chief A.G. Smith, acting as secretary, and the directors of the Six Nations Agricultural Society, with the Chiefs of the Six Nations Confederacy Council, Missionaries, and the Department of Indian Affairs acting as advisors. The mandate of this League was threefold: to fill the labour shortages on Six Nations’ farms, to locate land that was not being used and to bring it into production and, finally, to assess whether or not Six Nations’ farms could increase their production.

The League also oversaw seed distribution; ensuring that all farmers would have seed to plant.[4] According to the Department of Indian Affairs agricultural representative R.H. Abraham, Six Nations farmers should plant spring wheat, clover, and beans, as “a bushel of beans was worth as much in feeding value as three bushels of wheat. A pound of beans was worth as much as a pound of beef or any meat.”[5] It was Chief A.G. Smith’s hope that the Six Nations would respond to the Production League with the same enthusiasm that their soldiers had when they enlisted during various recruitment drives.[6] Although the response to the Six Nations Production League was positive, it was still noted in their March 1918 meeting that labour shortages on Six Nations farms continued to be a problem.[7]

The shortage of labour on Six Nations and Brant County farms reached a crisis point in April 1917 when the call went out for women to help on the farms and fields of both areas. The plea was dire, as the language used to describe the situation in Brant County was strong. It was said that there would be a ‘literal famine’ if people did not go to the fields to till the land and produce ‘foodstuffs.’ For Six Nations, female labour was organized through the Six Nations Production League,[8] while within Brantford and Brant County, the Women’s Patriotic League was the central location through which women were required to register. In July 1917, the situation in Brant County was more critical as stories circulated of hay, alfalfa and clover being cut, lying in fields, and exposed to the weather, which had turned rainy and cold. So vital were women’s contributions to the “Greater Production” push, that it was described as ‘noble work’ by the Canadian government with hopes to encourage more women to ‘do their bit’ in the Great War.

Even children were being recruited to help with the harvest. The Six Nations School Board Truant Officer, Harry Martin, noticed as early as November 1916 that many of their student absences were caused by children either staying at home to work on their family’s farm, or working out in the Niagara area helping bring in their harvests.[9] In 1917, school board members, Rev. George Carpenter and Andrew Staats passed a motion that children twelve years old and up would be exempt from school during seeding season as long as parents had work for them to do. For the sake of labour shortages on Six Nations farms, the motion passed.[10]

So desperate was the situation that money was being given to farmers of Brant County to hire and pay workers who were ‘competent and otherwise.’ High wages in the agriculture sector ($60 per month + board) rivaled those in the city.[11] Despite these high wages, there was still a shortage of help on the farm. Brantford and the surrounding areas were struggling to make agriculture (rural areas) and industry (urban areas) flourish simultaneously.

[1] Specific farmers who were referenced in these communities include: Sales, Cox, McClellan, Cleghorn, Vanevery, Clarke, McEwen, and Brooks. In Paris, Richard Sanderson and Fred Luck are mentioned.

[2] The Brantford Expositor, October 14, 1914.

[3] Mourad Djebabla, “’Fight or Farm’: Canadian Farmers and the Dilemma of the War Effort in World War One (1914-1919)” Canadian Military Journal, 13, 2 (Spring 2013): 66 http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol13/no2/doc/Djebabla-Pages5767-eng.pdf

[4] The Brantford Expositor, April 20, 1917.

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

[7] The Brantford Expositor, March 23, 1918.

[8] The Brantford Expositor, April 20, 1917.

[9] Report of Harry Martin (Truant Officer), November 15, 1916 (RG10 (Indian Affairs), Vol. 2010, File 7825-4, Reel C-11133, Title: Six Nations Reserve – Minutes of the School Board).

[10] Minutes of the Six Nations School Board, April 11, 1917 (RG10 (Indian Affairs), Vol. 2010, File 7825-4, Reel C-11133, Title: Six Nations Reserve – Minutes of the School Board).

[11] This was equivalent to $100 made by urban industrial workers.